Dealing with the paradox of choice in innovation

In a video made famous in 2007, when TED Talks still seemed amazing, Barry Schwartz made the case for limiting options and choices all around us. Especially in retail and marketing.

The paradox of choice stipulates that while we might believe that being presented with multiple options actually makes it easier to choose one that we are happy with, and thus increases consumer satisfaction, having an abundance of options actually requires more effort to make a decision and can leave us feeling unsatisfied with our choice. (...) Instead of increasing our freedom to have what we want, the paradox of choice suggests that having too many choices actually limits our freedom. - from The Decision Lab

The viral idea of the paradox of choice was born (and yes, the book became a best-seller too).

So sure, as with many American business ideas, it's all about overselling a core concept. Not that the insight doesn't have merit, but it's more the relentless lack of nuance that gets old very quickly. Without entering into the debate of knowing if the behavioral research at the core of the claim was legit or not, how should you decide how to apply this concept – and we'll see right after why it's so important for innovators?

The more complexity and the more understanding, the more choice might be necessary. Whereas, as Barry Schwartz explained, picking milk in a supermarket shouldn't force you to browse at 120 options.

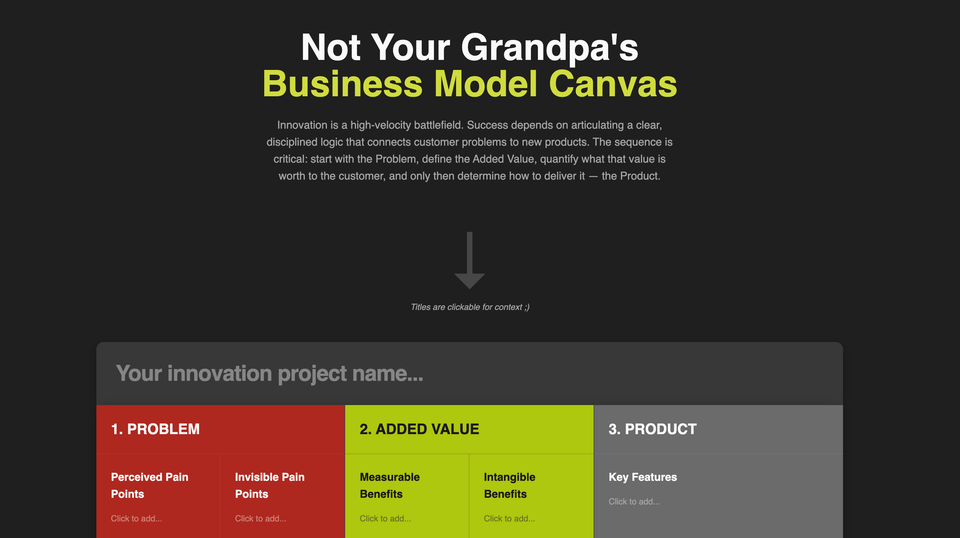

In my experience, when helping a customer formulate an offer for an innovative product (in B2B or B2C), I follow this simple heuristic:

- 80% Of the time, start with a focused three-tiers offer (ABC), where A is a simple version, B is the core offer, and C a premium/fully upgraded version. If you're slightly off (which is often the case), it's easy to transition to BCD (upsell) or XAB (downsell).

- Then, 15% of the time, if we're on a breakthrough claim or state-of-the-art technology, then go bold with only one flagship offer (think Apple or Tesla).

- Lastly, and only maybe 5% of the time or less, if we're in a high-level B2B offer dealing with a complex company process, only then I would consider a tailor-made approach akin to consulting (being aware that we quickly get diminishing returns when trying to extend customization too far).

What will not work for sure is not resolving the number of choices a customer should face and letting him decide. Not convinced? Just try to buy a computer online from Dell.

All this is a general principle when trying to sell something to someone. But as I was inferring, it's even more critical for innovators.

Because when launching a product that your market doesn't fully understand yet, you need to find the fabled product-market fit. The right formulation of an innovation that will solve enough of a market's problem, that said market would want to throw money at you to get it. And making this match should start with an offer as compact as possible so that you get the clearer feedback possible, as quickly as possible. Collecting market feedback from elusive early adopters will be impossible if you spread your innovation offer too much.

The less choice your offer, the clearer the product-market fit validation you'll have. And yes, this includes the price discussion. Always.